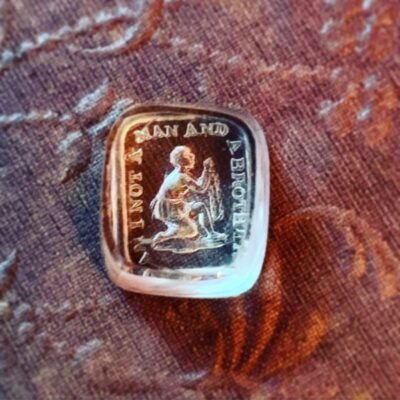

While most Americans may recognize Wedgwood jasperware by sight, few know that its creator Josiah Wedgwood ardently opposed slavery. Wedgwood, the English potter, advocated for the abolition of this evil practice from 1787 until the end of his life in 1795. Fewer still know that his efforts extended to America. His dissemination of medallions depicting an enslaved African man bent on one knee would, for a time, be seized upon as the ideal emblem for “promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom.” How could anyone see this image and not be reviled by the horrors and oppression of the slave trade?

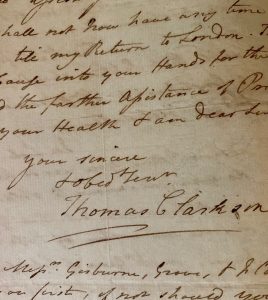

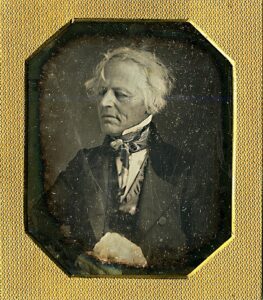

Wedgwood was a successful manufacturer in constant contact with British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. Clarkson was the author of a seminal essay in 1785 “Is it lawful to enslave the unconsenting?” and his fervor quickly attracted the admiration of American revolutionary and anti-slavery advocate John Jay. Jay entreated Clarkson to become an honorary member of the newly formed New York Manumission Society along with the Marquis de Lafayette and Granville Sharp. The correspondence of Jay, Clarkson, and other decriers of slavery like William Wilberforce suggests an intent to align the young New York organization’s anti-slavery platform with parallel movements in France and Britain.

No one knows with certainty the identity of the artist who created the “AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER” design for Clarkson’s Anti-Slavery Society. A sculptor at Wedgwood’s factory named William Hackwood is thought to have modeled the supplicant figure in shackles. But Wedgwood took it upon himself to manufacture many hundreds of cameos from the drawing for distribution at his own expense. Some were sent to Benjamin Franklin in 1788: “I enclose for the use of yourself & friends a few cameos, on a subject which I am happy to acquaint you is a daily more & more taking possessions of men’s minds on this side of the Atlantic as well as with you.” Franklin gifted one of these cameos to John Jay.

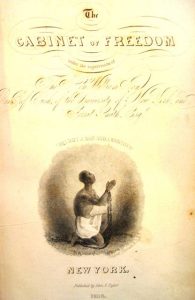

Wedgwood would not live to see Britain’s Bill of Abolition of the Slave Trade passed in 1807 but the kneeling slave design would live on as an eloquent and much copied symbol of the desperate need for social reform. The composition appeared stamped on the frontispiece of Thomas Clarkson’s 1836 “Cabinet of Freedom.” This collection of antislavery papers was assembled under the “supervision of the Hon. William Jay,” John Jay’s youngest son and an influential abolitionist in his own right. Even William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper “The Liberator” adopted the image for its masthead.

Though the individuals who invoked the kneeling slave symbol held the purest of objectives, over time the image backfired. It did not communicate the resilience, nobility and humanity of the men and women it purported to lift up. Like many images that lose their power or original meaning through overuse or subversion, Wedgwood’s kneeling slave ultimately contributed to sustained and pejorative views of black men and women as inferior, something Wedgwood could not have intended or anticipated.

That said, the motto behind this iconography, “Am I Not a Man and a Brother” is resurgent. It is suddenly appearing all over social media platforms like Twitter and Instagram today because at its core it is a universally understood plea for equality and justice.

— Suzanne Clary