The Jay Heritage Center is honored to share news that it will be displaying a rare internment camp painting by master sumi-e painter and great post-war abstractionist Koho Yamamoto at the 1838 Jay Mansion this September 29- October 1. The display will be added to a weekend-long collaboration called Friendship Through Japanese Arts and Culture made possible through a dynamic partnership with the Japan Society of Greater Fairfield County (JSFC) and the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah. The event supports JSFC’s dedication to building knowledge and mutual understanding between Japanese and Americans through educational, cultural and philanthropic programs. The weekend will kick off with the dedication of a Higan cherry tree allée that is to be planted as part of the Jay Estate Gardens and also include a spectacular flower show hosted by International Ikebana New York. The painting exhibit and flower show will be open to the public as part of New York State Park’s Hudson River Valley Ramble weekend and complement the Jay Heritage Center’s annual family fall festival, Jay Day.

FLOWER SHOW AND YAMAMOTO PAINTING EXHIBIT HOURS – FREE ADMISSION

Friday: Flower Show at the Wachenheim Center from 3pm – 5:00pm; Higan Tree dedication 5:00 pm in Jay Estate Gardens; Yamamoto Painting Exhibit Opening Reception at 5:30 at the Jay Mansion. Enjoy tea ceremony on the porch of the Jay Mansion by Urasenke School, teacher Suzuki Miyako Somi and her students. Everyone is welcome and the reception is free and open to the public. (Rain location – Wachenheim Center)

Saturday: Ikebana Flower Show at the Wachenheim Center from 10am -5pm; Yamamoto Painting Exhibit at the Jay Mansion 10am – 5pm

Explore the Jay Estate Gardens and exhibits on your own or guides will be available to give tours and provide information. In the Jay Mansion, learn more about Koho Yamamoto’s painting depicting an internment camp scene. Additional activities include wares from pottery artists Namiko Kato and Hiroko Yokotagawa:

https://www.instagram.com/

https://www.instagram.com/

and Obi-Obi: https://www.instagram.com/

“Obi-Obi” will be joining us in the afternoon 12-4pm. This volunteer and craft group upcycles kimono fabrics and obi belts into unique home décor and bags. Also, Saturday afternoon, listen for the sounds of the shakuhach! Mr. Nori Ishikawa will be playing at the ikebana exhibit, Japanese, Jazz, or western style.

Sunday: Ikebana Flower Show at the Wachenheim Center from 10am -4pm; Yamamoto Painting Exhibit at the Jay Mansion 10am – 4pm

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Topaz Museum acquired Yamamoto’s painting with funds generously donated by Ms. Jackie Alexander who spearheaded the project and made the acquisition possible. Ms. Alexander is the president of the Japan Society of Greater Fairfield County and the secretary of the Ikebana International New York Chapter. She has a personal association with Topaz – her grandparents and many relatives were interned at the Topaz Internment Camp during the war and one of them passed while staying at the camp. Her father was an issei living in New York and taught Japanese to soldiers at Yale – he was allowed to visit Topaz for the funeral.

The painting will be on view to the public beginning Friday, September 29th at the Jay Mansion. Additional programs will be planned and coordinated with the Japan Society of Greater Fairfield County in the coming year after which the painting will travel next to the Topaz Museum where it will be come part of their permanent collection.

Koho Yamamoto was born in Alviso, California, in 1922 and spent her early elementary school years in Japan, returning permanently to live in the United States at age nine in 1931. Her father was a calligrapher; her mother died when she was just four. During the Second World War, Yamamoto was forcibly incarcerated with her father and siblings in three of the prison camps established by the American government for residents of Japanese ancestry living on the west coast of the United States: the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, Calif.; the Topaz Relocation Center near Delta, Utah; and the Tule Lake Segregation Center in Newell, Calif.

At the Utah internment camp in 1942, Yamamoto studied with the renowned artist, Chiura Obata, who was also confined at Topaz. In recognition of her skill and artistry in sumi-e, Professor Obata conferred upon her the name ‘Koho’, which is a Japanese tradition of denoting artistic lineage from masters to their pupils. Obata’s name translates to ‘A Thousand Harbors’ and Koho translates as ‘Red Harbor’.

Yamamoto was also part of the Topaz Poppy Club and composed tankas (short poems) as one of the youngest members of the club at age 20. In spite of the rigors of life in the camp, Yamamoto’s artistry took shape and flourished under a generous and talented teacher. She says that they had a lot of time in the camp, which was put to good use by the artists. One of the tankas that she wrote in the camp says – “Sometimes I wish I could jump into the turmoil of humanity and live life seriously.”

Besides painting the traditional sumi-e subjects taught by Prof. Obata at the camp’s art school, Yamamoto also sketched and painted the scenery around the camp. Her paintings from this time capture the loneliness of camp life. Yamomoto painted the barrenness of the scenery with rows of barracks, guard towers and sparse vegetation dominated by the big skies of the dusty Utah desert. The Blue Koho Camp Painting (c. 1943) in the National Museum of American History’s collection, shows a crescent moon rising on a barren camp, and an Untitled painting (1944) from Cantor Arts Center at the Stanford University, California, has a brilliant desert sky over rows of barracks that appear insubstantial and forlorn.

In the August of 1943, Yamamoto and her family were transferred to Tule Lake Segregation Center in California, and her poetry club friends bid her farewell with messages of good luck written in the tradition of yosegaki (sideways writing).

After the war, Yamamoto moved to New York City and studied at the Arts Students League. She took up various jobs to support herself before founding an eponymous school on MacDougal Street in 1974, where she taught generations of students until 2010 when the school was closed. Though she is a dedicated teacher of traditional sumi-e subjects, her own work is inspired from the ideas and thoughts developed in Postwar Abstract Expressionism in New York, where she has lived since 1945. Yamamoto has exhibited in numerous shows over her long illustrious career, most recently at the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum and at the Leonovich Gallery in New York. Yamamoto’s exceptional career was recently profiled in the New York Times.

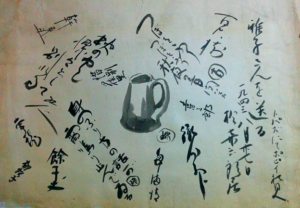

The artwork on exhibit at the Jay Heritage Center was painted in 1978 at Yamamoto’s MacDougal Street studio in New York. It shows the Topaz Internment Camp enclosed by barbed wire with an American flag, a guard tower and the barracks in the distance. Three decades after the forced imprisonment of her generation of Japanese-Americans, Yamamoto in her mature style painted the memories of loneliness and isolation from her time at the internment camps. Today the Topaz Museum Board owns and preserves the residential area of Topaz, comprised of 640 acres of the 19,000-acre internment site. The Museum is interpreting the impact of Topaz on the internees and their families while also educating the public in order to prevent a recurrence of a similar denial of American civil rights. This collaboration would not have been possible without the help of Ms. Jane Beckwith, founding board member of the Topaz Museum, Jaya Duvvuri, an artist, curator and student of Ms. Yamamoto, and support from the family of Jackie Alexander.

Generations of the Jay family, most notably landscape architect Mary Rutherfurd Jay, had a longstanding respect and admiration for Japanese arts and culture. Jay not only traveled to Japan and lectured frequently about Japanese life and gardens, she also participated in activities of the Japan Society of New York which was founded in 1907 to promote friendly relations between the United States and Japan. This collaboration between the Jay Heritage Center and the Topaz Museum honors that tradition.

Readers can follow Koho Yamamoto on Instagram at @kohoyamamoto.

Topaz Internment Camp, 1978, Koho Yamamoto, ink on paper