By Suzanne Clary

When we invited Joseph McGill, Jr., founder of the Slave Dwelling Project, to speak at the Jay Heritage Center, one of the first things we told him about were remains of an 18th-century cabin buried in the shadow of the Jay Mansion. Uncovered in 2017 by Eagle Scouts under the discerning gaze of archaeologist Dr. Eugene Boesch, the structure’s collapsed brick chimney was found several feet from a horse chestnut tree near the main house. Could the structure they unearthed have been a slave dwelling? Could it be a place where men, women and children owned by the Budd and Jay families woke each morning and slept each night while living in forced servitude? Was it built with their own enslaved hands?

We had searched for it for more than a decade, relying on two drawings in our archives as divining rods. We knew it was close to a stable and close to the gardens. Ground penetrating radar missed it, but repeated old-fashioned shovel tests located it. Its discovery makes the narratives of real people, not chattel—Mary, Plato, Yaff, Clarinda, Caesar Valentine, his son Caesar Valentine and many before them—that much more accessible. *

At first glance, the excavated remnants called to mind a building in nearby Port Chester at the Bush-Lyon Homestead that was still above ground, standing in plain sight. How did these two testamentary objects, indelible proof of Northern slavery, compare with each other? How did they compare with dwellings Joseph McGill had seen in more than 23 other states in our nation? What wisdom could he share about rallying support to preserve these authentic cultural resources?

Unlike the Jay Estate, which is still buffered by over 160 acres of land and set far back from the Post Road, the Bush-Lyon Homestead sits directly on a busy thoroughfare, King Street. Behind it is a wooden shack that is likely the same age as the main house, which was raised between 1720 and 1750. That would make it the oldest extant slave dwelling in Westchester County. Believed to have confined at least two men of African descent, known only as Jack and Harry, this 10’ by 10’ dwelling has been stained and repainted rooster red many times. It has been shingled and re-shingled with a patchwork of materials that still can’t seem to keep the rain or the squirrels out. A large flat stone marks the threshold. The front door is padlocked.

In 1931, Westchester journalist Elizabeth Cushman noted how its companion, the white clapboarded home of Abraham Bush and Ruth Lyon, was lovingly maintained and carefully curated with Revolutionary-era artifacts while the other buildings were crammed with less important things: “The wide boards in this front hall…cover the secret passage that led underground to the outbuildings still standing—the old slave house, now crowded with relics of farm industry, and the old carriage house.”

Sixty years later, in 1991, the same building was commandeered by the Port Chester Highway Department as space for their equipment—sawhorses, traffic cones, oil cans etc. NAACP President Doris Reavis appealed to then Mayor Peter Iasillo to give the small wooden “home” the same dignity as the main house. Her requests were rebuffed. Dr. Larry Spruill, lead research consultant for Westchester County’s inaugural African American Heritage Trail (which has 13 sites including the Jay Estate) spoke to the New York Times in 2004. While he strongly recommended that the King Street site be included on the trail and called it “priceless in a historical context,” there was no funding for restoration and interpretation of the Slave Quarters.

When I first laid eyes upon the place, it was 2011. I could only observe it from the exterior. Did the slave dwelling at the Jay Estate once look like this? One small high window seemed to be the only source of light for its occupants. It was steps away from a well but there was no apparent chimney for warmth. It was sandwiched next to two much wider and taller boxes that may have once been a corn crib and a barn. I tried to learn more about its caretakers and found out that the Port Chester Historical Society that ran the Homestead had disbanded. Fortunately, I met Joan Grangenois-Thomas and her husband Dave Thomas. This incredible husband and wife team had helped initiate restoration efforts at Rye’s historic African American Cemetery. All three of us had crushing workloads but couldn’t let go of the idea that the Bush-Lyon Slave Quarters could be saved. We told anyone who would listen that something had to be done—but what? Where would the money or volunteers come from?

Five years passed with little to no progress. Appreciating the urgency of saving this threatened dwelling, Erin Tobin and Fran Gubler from the Preservation League of New York State (PLNYS) agreed to make a visit down from Albany to the site in November 2016 to offer technical advice. We were joined by the town attorney from Port Chester who graciously arranged access to see the interior. We braced ourselves for the worst. As the door swung open, my reactions were revulsion and shame. How did we ever treat human beings like this? This structure had survived despite the urban pressures surrounding it. It had a powerful story to tell if it could be preserved. Frustration was channeled into hope and resolve. The building was filled with garbage, rodent droppings, tattered books, and clothes but wasn’t unsalvageable. A map inside the main homestead was discovered that clearly denoted at least one of the outside buildings as slave quarters. The group agreed that a strategy was needed and perhaps there were opportunities for applying for grants and finding other stabilization funds.

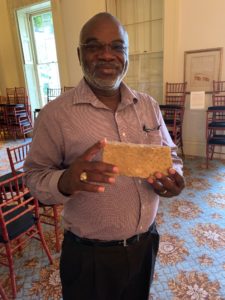

In addition to money, preservationists need three things: passion, perseverance and patience. It is now 2019 and perhaps this is the year that great things happen. On Sunday, June 9, over 90 people attended compelling presentations by Dr. Spruill and Joseph McGill at the 1838 Jay Mansion, steps away from our own archaeological dig. The audience listened to how they are actively resurrecting the real lives of African American women and men through scholarship and advocacy. Afterwards, many agreed that examining the lives of Jack and Harry in Saw Pitt (the original name for Port Chester) would be meaningful in understanding another facet of Westchester County’s African American narrative.

Could the tiny building where these two enslaved men woke and slept finally be considered as a 14th site on the Trail? The recent swell of support from a diverse swathe of the community is encouraging. It is a vivid reminder that places like the Jay Estate and the Slave Quarters at the Bush-Lyon Homestead, and the stories of the people who lived there, still matter to us today.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

* John Jay’s father Peter, master of the family’s country seat, owned eight individuals according to a 1755 census. We are constantly scouring family letters for the names or actions of these uprooted men and women. We look for their imprints each time one of our digs reveals a shard of salt glazed pottery that they may have touched. Studying their surrounding community is an active part of what we do and have been doing for more than 20 years.

John, who grew up in Rye and ultimately inherited the estate, also became a slaveholder. Unlike his father, he came to believe that slavery was morally wrong and glaringly inconsistent with our fight for independence. John’s first efforts to discontinue slavery through legislation in 1777 and 1785, were opposed and unsuccessful. Undeterred, he continued to try to find legal resolutions to apply justice. As President of the NY Manumission Society in 1785, John helped defend the rights of enslaved men and women who were threatened by kidnapping for sale in other states. He helped establish the first African Free School in 1787 to prepare children for citizenship. Finally, as Governor in 1799, John signed New York’s Gradual Emancipation Act into law. Nonetheless his words and actions were contradictory; a census proves he still owned one individual at his retirement home in Bedford as late as 1810. A 1792 letter written in his own hand reveals his struggle to reconcile legal rights and inalienable human rights – how could anyone especially our nation’s first Chief Justice have faltered on such an issue?

His children advanced his anti-slavery legacy more decisively. His sons advocated to accelerate the manumission timeline and supported facilitating the escape of fugitives. His daughters established a home for destitute and aged Americans of African descent. In 1821, his eldest son, Peter Augustus Jay, defended the rights of voting suffrage for freed men at New York State’s Constitutional Convention. When another delegate declared “the intellect of a black man is naturally inferior to that of a white man,” Peter Augustus emphatically rejected the statement as “completely refuted and universally exploded.”

As for slavery at the Jay Estate in Rye, the last person to be manumitted was a man named Caesar Valentine owned by John Jay’s sister-in-law Mary. Only after her death in 1824 was he freed. Seven years after John Jay died, the 18th-century farmhouse that Caesar would have known for most of his life was torn down. A new Greek Revival house whose architecture drew upon the vocabulary of democracy rose in its place in 1838. Many of the old colonial buildings appear to have also been razed at this time. Fragments were re-purposed. Five free black servants, two men and three women, still lived and worked at the Jay Estate in Rye – by 1840, that number had dwindled to one.

As for slavery at the Jay Estate in Rye, the last person to be manumitted was a man named Caesar Valentine owned by John Jay’s sister-in-law Mary. Only after her death in 1824 was he freed. Seven years after John Jay died, the 18th-century farmhouse that Caesar would have known for most of his life was torn down. A new Greek Revival house whose architecture drew upon the vocabulary of democracy rose in its place in 1838. Many of the old colonial buildings appear to have also been razed at this time. Fragments were re-purposed. Five free black servants, two men and three women, still lived and worked at the Jay Estate in Rye – by 1840, that number had dwindled to one.

In 1847, Caesar died of apoplexy at the age of 60. He was buried somewhere on the property in an unmarked burying ground. Research about his life and the lives of all the enslaved and freed people at the Jay Estate continues.