John Jay

In his 1973 book “Seven Who Shaped Our Destiny: The Founding Fathers as Revolutionaries,” historian Richard B. Morris famously credited seven men as being America’s Founding Fathers because of their key roles in shaping our government: John Jay, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison.

Rye

John Jay was born in Manhattan on December 12, 1745. He was presciently named for his uncle John Chambers, a well-known lawyer and Supreme Court judge. John’s father Peter was French Huguenot and his mother Mary Van Cortlandt was Dutch. His grandfather Auguste had been a prosperous merchant and married into the Stuyvesant family. Though the Jays had excellent real estate holdings in lower New York, the family moved to Westchester to escape the scourge of a smallpox epidemic in New York City that had left one child dead and two irreversibly blinded.

Rye was a safer, greener haven for the Jays. Jay’s father Peter bought an initial messuage of 250 acres in 1745 from John Budd 4th followed by several more purchases. The fresh air and expansive country seat with meadows and gardens overlooking Long Island Sound promised a healthier life and future. Baby John was only 3 months old when they settled there. (Original watercolor and ink wash of the original Jay family home known as “The Locusts” – Gift of Emily and John Clarkson Jay)

Of Mary and Peter Jay’s 10 children, 4 sons and 3 daughters survived into adulthood: Eve, Augustus, James, Peter, Anna Maricka, John and Frederick. Both Peter and Anna were blind. Augustus had significant learning disabilities. John, the eighth child was notably bright – his father noted that he “takes to learning exceedingly well.” His mother Mary Van Cortlandt taught John at home until he was 8 years old at which time he attended school in New Rochelle for a period of three years with a French Huguenot pastor, Pierre Stouppe. In 1756 John returned to Rye where he was again tutored at home by his mother and an instructor, George Murray.

On August 29, 1760, Jay entered Kings College (today’s Columbia University) where he would continue studies in Latin, Greek and philosophy but also begin to contemplate a future legal career. Not only did Jay successfully enter into a legal apprenticeship with Benjamin Kissam following his college graduation in 1764 but he also won one of his first successful negotiations – he craftily coaxed his father into giving him permission to have a horse explaining that it would make it much easier for him to come home every two weeks to Rye to visit! When the Stamp Act compelled John and many other lawyers to strike in defiance of British law, he returned again to Rye to live from 1765 to 1766, and immersed himself in re-reading the classics.

Rye was a place of both contemplation and celebration for the young attorney most famously following his return from negotiating the end of war with Great Britain (see below). Jay’s character was influenced by this touchstone throughout his formative youth and he would return to it throughout his career to be with his wife Sarah Livingston, his parents, his siblings and eventually his own children.

Rye is the place to which John Jay returned after negotiating the Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War.

“Jay quitted Paris in May, Seventeen Hundred Eighty-four, having been gone from his native land eight years. When he reached New York there was a great demonstration in his honor. Triumphal arches were erected across Broadway, houses and stores were decorated with bunting, cannons boomed, and bells rang. The freedom of the city was presented to him in a gold box, with an exceedingly complimentary address, engrossed on parchment, and signed by one hundred of the leading citizens.

Jay spent just one day in New York, and then rode on horseback up to the old farm at Rye, Westchester County…that evening there was a service of thanksgiving at the village church, after which the citizens repaired to the Jay mansion, one story high and eighty feet long, where a barrel of cider was tapped, and ‘a groce of Church Wardens’ passed around, with free tobacco for all.

John Jay stood on the front porch and made a modest speech just five minutes long, among other things saying he had come home to be a neighbor to them, having quit public life for good. But he refused to talk about his own experiences in Europe. His reticence, however, was made up for by good old Peter Jay, who assured the people that John Jay was America’s foremost citizen; and in this statement he was backed up by the village preacher, with not a dissenting voice from the assembled citizens.”

Rye has been known as the hometown of John Jay for over 270 years.

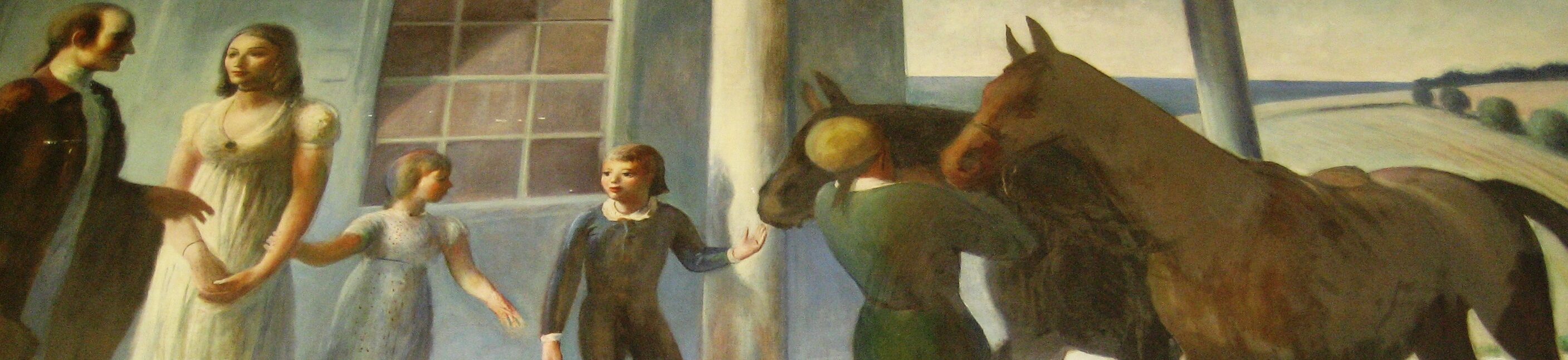

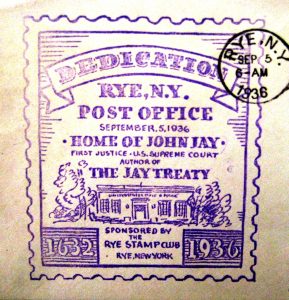

Cognizant of Jay’s integral role in the shaping of American history and his Rye roots, Congresswoman Caroline O’ Day, a close friend of President and Eleanor Roosevelt, suggested during the WPA era that this New York native be the subject of a mural commission by Guy Pene du Bois inside the new Rye Post Office that was being built. O’Day’s efforts and the issuance of this stamp cancellation to commemorate the ribbon cutting and opening of the facility on September 5, 1936 both created a renewed focus on Jay:

“Considerable interest in the life of John Jay has been awakened by the mural on the wall of the Rye Post Office depicting the departure of the famous patriot from the Jay homestead on the Post Road.” Rye Chronicle, February 11, 1938.

Du Bois’ masterpiece depicting Jay’s original farmhouse (where he grew up and which he later owned between 1813 and 1822) is still there today in the lobby. The Rye Post Office itself was renamed the Caroline O’ Day Post Office in 2009 thanks to the cooperative efforts of Congresswoman Nita Lowey and Rye resident and historian, Paul De Forest Hicks

Jay established a burying ground for his family and his descendants in Rye, choosing one of the meadows there for his own repose as well. Because of their association with the Stuyvesant family, the Jays had previously had a vault at St. Marks on the Bouwerie. In 1807, Jay had the remains of his wife Sarah Livingston and those of his colonial ancestors reinterred in Rye, establishing a private cemetery. Today, the Jay Cemetery is an integral part of the Boston Post Road Historic District, adjacent to the historic Jay Estate. The Cemetery is maintained by the Jay descendants and is closed to the public.

Justice Harry Blackmun in his own visit to the Jay’s Rye home remarked:

“I was impressed with the house, with the lawn, with the great trees, some of which are now gone, and with the vista down to Long Island Sound. It was a place that struck me then as symbolic of what was impressive about certain aspects of the latter part of the eighteenth century – gracious living and status, to be sure, but coupled with a sense of responsibility, particularly to government and to the art of getting along together…

It must be a matter of great pride to be members of an old and distinguished family that contributed so much to early America, that believes in education and leadership then and now, that has sensed the merits, almost the sacredness, of family ties and of what is expected of its members in each generation. I am certain that all of us who are here today join in saluting the Jay family for its significant contributions that meant so much when this Nation that we all love was in its precarious infancy…

We are grateful for John Jay’s having been a part of our national heritage. He was a rock to which the Nation could cling at a time when it might have drifted apart and become helpless just when rich promise lay ahead.”— Harry A. Blackmun