Photo credits: JHC Collection

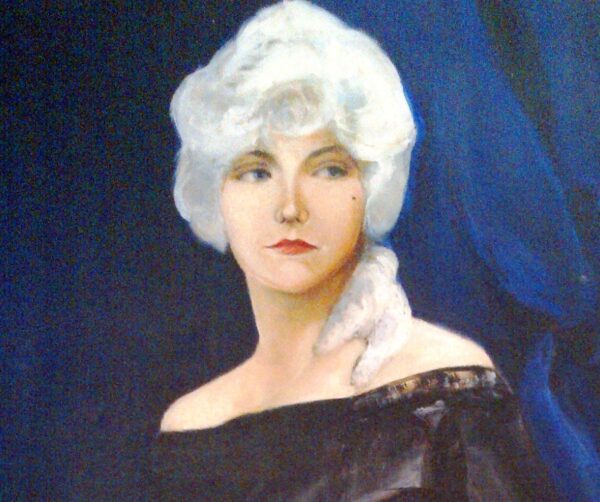

One of the most striking portraits in our collection is this 20th century painting of Louise Tormey Kline Jay. Louise’s Lenten-hued, off-the-shoulder gown, either an heirloom or a revolutionary era costume, looks even more sumptuous set against midnight blue drapery. A powdered-white wig looks uncomfortably heavy – it overpowers her face but can’t diminish her concentration as she poses for the artist.* Her expression seems to say “I have arrived, ” and indeed she had. Louise was one of many proud immigrants to marry into the Jay circle. She wasn’t Dutch or French or English. Her family came from Ireland.

How did the daughter of Irish immigrants find herself in Knickerbocker society? Louise’s mother Mary Tormey was born in Massachusetts but her parents were from Ireland. Her father Michael Cleyne emigrated from Ireland sometime before 1870 and found work as a moulder in an iron foundry in Hartford, Connecticut. The city was at the epicenter of American industrialization through its dominance in the manufacturing of firearms and its production of woven goods at textile mills. The Cleynes settled in Hartford on Broad Street (which today borders the Trinity College campus) and their neighbors were blacksmiths, machinists and silk weavers. Some were native-born Connecticut “nutmeggers.” Others hailed from Scotland and what was then called Prussia, and Bohemia (part of today’s Czech Republic). After 1880 Louise’s father changed their name to Kline – Kline is of German/Dutch origin and might have been more acceptable in certain circumstances where prejudices against the Irish began to churn.

Both of Louise’s parents died by the time she was only 18 leaving Louise and her 3 surviving sisters and 3 brothers poised to pursue different paths. Louise’s closest sister Irene, nicknamed Rene, was the first of the siblings to move away. She married into a prominent New England family, the Southmayds, and went to Springfield, Massachusetts with her husband Leon. Meanwhile, Louise found clerical work at an insurance firm eventually moving to her own apartment in New York’s upper East Side while her two older sisters Marie and Lillian Agnes became accomplished musicians. Marie, a contralto, and Lillian, a soprano, studied and sang first at their hometown church. Lillian went on to hone her vocal talents at Yale and later at the Sorbonne in Paris. They both had professional careers and often performed together and with groups like the Gaelic Society. They also participated in efforts to “spread a knowledge of Ireland’s literature, music, art and early civilization.” At one commemoration of the 125th birthday of the poet, lyricist, patriot and Roman Catholic Tom Moore, the sisters entertained the audience with renditions of familiar Irish melodies that paid homage to their Celtic ancestry: Banks of Banna, Brink of the White Rocks and Lament of the Milesians. Their brother Joseph Jerome marched to the thrum of a different rhythm – he started out as a tool maker, stayed in Connecticut and made a living as a conductor with the New Haven Railroad. Another brother Frank lived with Joseph.

In 1926, when Louise was 31 years old, her sister Rene and brother-in-law announced Louise’s engagement to John Jay in the Hartford Courant. A photo of Louise in profile captures her Jazz Age, nape-revealing, shingle bob hairstyle. We currently have no records of how they met – was it at a concert? Who introduced them? John, a Yale graduate and businessman, 20 years her senior, was a successful broker at the time and had never previously married. He was the last lineal descendant of John Jay to be born at the Jay Estate in Rye – his father had been an Episcopal minister at Christ’s Church. Somehow the bachelor and the Irish working girl were brought together and made a match. But the couple would never have the opportunity to have their own children who might have been able to share with us the story of their “meet cute” – they were married only one year and seven months before John died suddenly in Cape Cod following an attack of acute appendicitis. He was 52.

Because John left no heirs, Louise became the primary recipient of his estate. After his death, she divided her time between Manhattan and Fairfield, Connecticut where she commissioned a beautiful French-styled home known as Pavilion de Chase. She travelled extensively with both her sisters and occasionally with her sister-in-law, the noted garden architect Mary Rutherfurd Jay. Proximity made it easy for the women to spend time together. In 1938, following her husband’s death, Louise’s sister Rene relocated to Bronxville in Westchester. Her other sister Lillian lived with her. Society pages tracked their seasonal baggage packing, rail jaunts and liner crossings between the Catskills, Palm Beach and Paris where Louise had homes. She never remarried.

Like many of the Jay descendants and their spouses, Louise valued education and philanthropy. While alive, she gave generously to various charities. When she died at the age of 73, she left funds for the Home for Incurables, a hospital for chronic diseases in the Bronx where her sister Lillian died in 1947. Today the institution is called St. Barnabas Hospital and it has one of the largest and oldest emergency residency programs in all of New York City and provides services to a diverse community including a Level II Trauma Center, Stroke Center and HIV/AIDS Center. Louise also established a scholarship in her late husband’s memory at Columbia University for the study of American History.

As an institution of learning and interpretation of our shared cultural heritage, JHC is grateful to Louise’s family for choosing to donate this portrait to us. The Kline family’s Irish-American legacy is just one of the many stories that an artwork like this can help us remember and share with visitors.

To read about another portrait of an Irish-American in our collection, that of William Kerin Constable, founder of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, click here.

–Suzanne Clary

* The artist is Helene Lucas Wood.